Blog

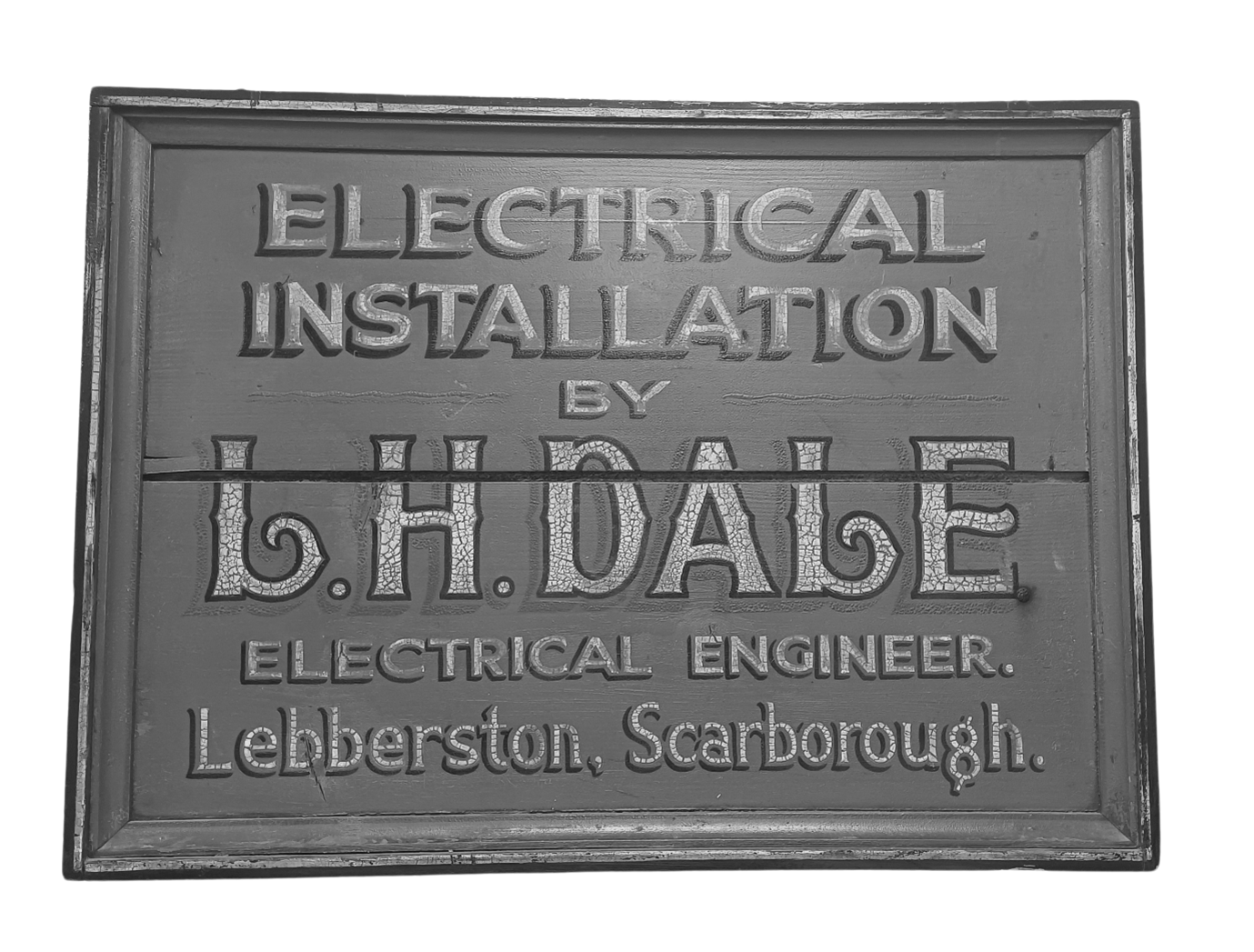

As the end of the Second World War approached in 1944, the founder of Dale Electric, Leonard Dale, formally ended his partnership with Peter Corner, with whom he’d collaborated to meet wartime munition infrastructure demands. Leonard returned his focus to the North Yorkshire farming communities that had long formed his business’s foundation, many of whom remained without access to the national mains electricity supply.

Post-war Britain was driven to restore civilian life, and as a part of this Leonard’s electrical engineering team began rewiring properties that had been requisitioned by the Air Ministry, such as hotels, Butlin’s holiday camp in Filey, and the Scarborough Spa, having originally been rewired for war purposes by Leonard himself. With more of a team, they had more workload capacity and could rewire more wartime buildings than Leonard had originally been able to, leading to the replacement of outdated 1930s circuitry.

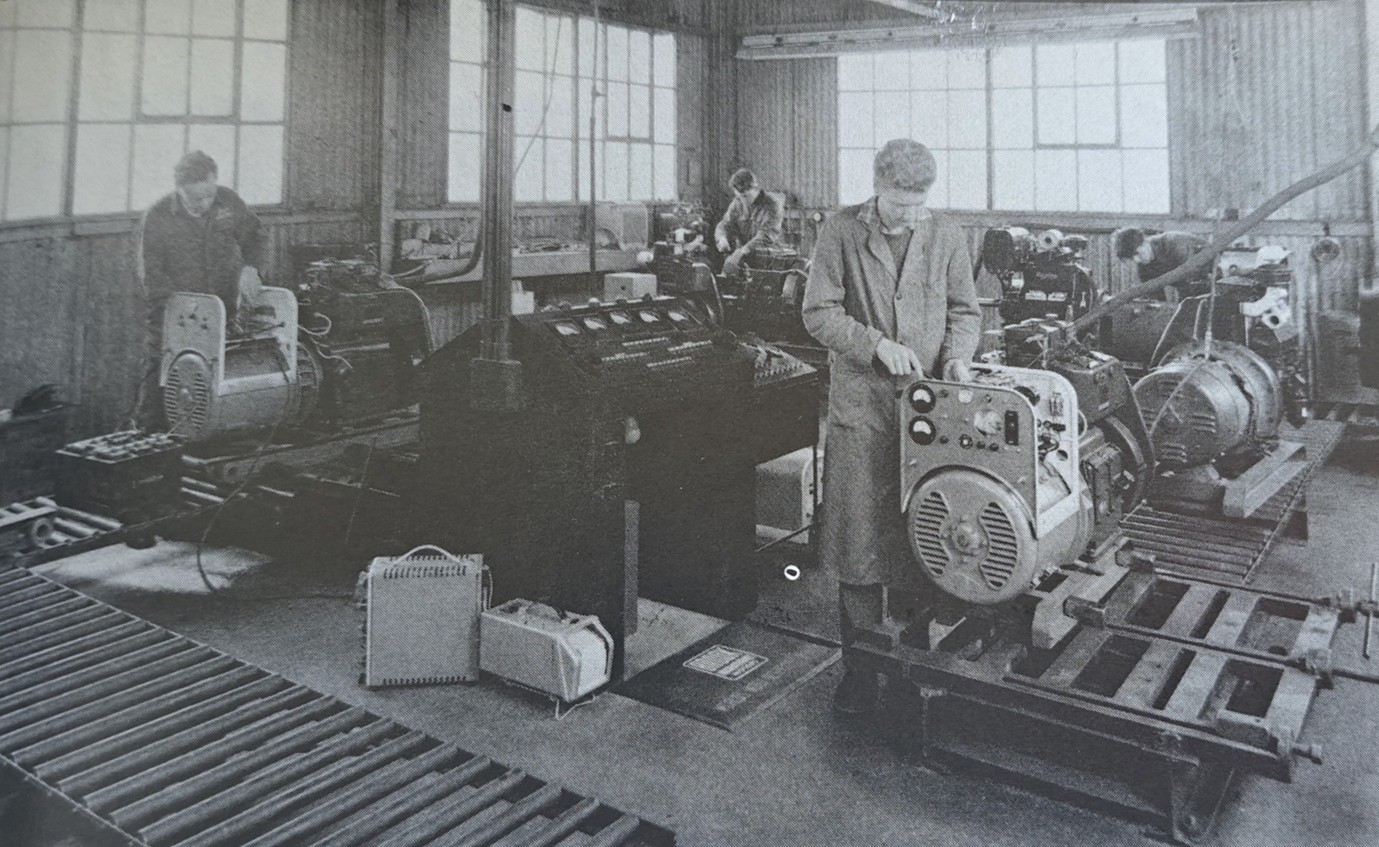

With more of a certain future, Leonard set his sights on repairing and servicing old generating sets. The shift prompted the expansion of a purpose-built workshop, depot and warehouse, an 80ft by 30ft facility constructed on his father’s land, pictured below. It held stock from motors to alternators, cables, and conduits, marking the beginning of Dale Electric’s domestic electrical contracting to small-scale manufacturing and service provision.

It held stock from motors to alternators, cables, and conduits, marking the beginning of Dale Electric’s domestic electrical contracting to small-scale manufacturing and service provision.

Around this time, Sidney Chapman, a former Hong Kong policeman who had survived over four harrowing years as a prisoner of war in a Tokyo shipyard, came to Leonard Dale for work. Malnourished and demobilised to Folkton, Leonard took him on temporarily but ensured he wasn't overburdened, instructing Geoff Race to assign him only light tasks. Sidney remained with Dale for 34 years, eventually becoming Works Foreman and earning a British Empire Medal in 1974.

The company’s return to civilian work created opportunities to reintegrate men returning from military service. Some brought with them valuable skills gained during the war. Jack Hoggarth, for example, joined the team in 1945 after being demobbed at age 22 from a King’s Royal Rifles motor battalion, where he’d developed expertise in petrol and diesel engine mechanics. His knowledge proved vital as Dale ramped up service and maintenance operations.

The company undertook the six-month endeavour of rewiring North Riding Training College, which had been occupied by the RAF since 1940. Meanwhile, other teams tackled the wiring of new housing estates in Scalby, and the conversion of screens and crushers to electric operation at Newbridge Limestone Quarries near Pickering, a key stone supplier for post-war motorway construction.

Generating set test bay at Gristhrope in the early 1950s

Generating set test bay at Gristhrope in the early 1950s

The growth of the business brought in new staff and a new operational model. Members of the service team rotated through fieldwork and workshop roles to ensure a multi-skilled workforce that could adapt to customers’ evolving needs.

To meet rural demand and provide a regional presence, Leonard opened several branch offices, starting in 1946 with Malton, followed by Driffield, Pocklington, Market Weighton, and Hornsea. After three years, these branches had rewired most large farms in the area. In a gesture that combined business pragmatism with generosity, Leonard gifted each branch to its manager, charging only for stock with a three-year repayment period. Staying true to his belief that business should be kind but unsentimental, the branches could not use the Dale Electric name.

Hand-painted L. H. Dale sign, an earlier iteration of Dale Electric

Hand-painted L. H. Dale sign, an earlier iteration of Dale Electric

Dale Electric (Yorkshire) Limited was formally incorporated in September 1947, with 20 shareholders and a switch to Barclays Bank. Between 1941/2 and 1946/7, turnover had grown twelvefold. Leonard’s response was to focus on the future, placing more emphasis on the design and manufacture of generating sets, a project that would take 4 years to perfect.

The first Dale Electric generator set was sold in 1948 to a Yorkshire wool merchant. Built with a diesel engine, alternator, and hand-crank starter, it powered lighting and milking equipment on a remote farm between Ravenscar and Robin Hood’s Bay. Leonard also created generating sets that matched public supply voltages to ease the future transition to grid electricity.

Dale Electric’s display at the 1950 Yorkshire Agricultural Society Show (Malton), highlighting the transition into generating sets

Dale Electric’s display at the 1950 Yorkshire Agricultural Society Show (Malton), highlighting the transition into generating sets

In the post-war shortage of materials, Leonard’s team crafted components like relay cores and coils in-house. Switchgear design became a key area of innovation. The first design required manual startup, while the second generation allowed automatic activation from any light switch, enabling effortless domestic and agricultural use.

Leonard also ventured into new products: electric welders with remote control (so operators could self-adjust voltage inside pipelines), diesel pump sets, and even boot-cleaning machines. Many ideas proved ahead of their time, commercially unviable in the post-war economy but later standardised, like the coin-operated boot polisher.

True to his ethos of profitability over sentimentality Leonard discontinued anything that didn’t meet the standard.

One innovation that stood the test of time was the Dale Earth Leakage Trip, developed after reports of fatal electric shocks at Hull Docks, where engineering workers using portable drills were exposed to dangerous current levels. The device, a compact box fitted with a four-pin socket, was designed to cut off any reverse current in under 20 milliseconds, dramatically improving safety on site. The original idea used a three-wire system with the neutral cable serving as neutral and earth, but this faced resistance from the Electricity Board. Leonard overcame the objection by switching to a four-wire design, which was ultimately patented by Dale Electric.

The Earth Leakage Trip sold well throughout the late 1940s and into the 1950s, until the widespread adoption of 110-volt centre-tapped-to-earth systems, limiting voltage to earth at just 55 volts, a safety standard derived from earlier American voltage norms, made such protective devices less critical. Formalised by the Electricity Supply Regulations (1988), and updated in the Electricity Safety, Quality and Continuity Regulations (2002), the Electricity Board backed Leonard’s original proposition of using the neutral cable as earth. Though the regulation shifted the market, Leonard’s safety-first mindset had already helped set a new benchmark for portable electrical equipment.

The post-war years at Dale Electric (Yorkshire) Limited were defined by a mix of ambition, pragmatism, and ingenuity. Leonard Dale laid the groundwork not only for technical excellence but for the company’s reputation as a business rooted in both community values and forward-thinking innovation. From rewiring war-torn towns to reimagining rural power supply, the legacy of this period shaped Dale Electric’s next great leap into national manufacturing prominence.

Generators | Uninterruptible Power Supply (UPS) | Battery Energy Storage Systems (BESS) | Contact Us